Thank you for this interesting contribution,

@Faye Walker. It caused me to actually have a look at the survey that Nancy L. Frey did. She conducted a survey between April 2015 and April 2016

to find out just how frequent and extensive mobile technology use was in practice.

She wrote an article about her survey but points out that she did not intend t

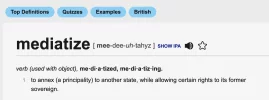

o publish an academic article but to use the data I extrapolated from it for my own work on the impact of the rise of the Internet on the pilgrimage experience. It is not written with an academic voice nor does it follow a strict academic style. It is a lengthy article. Both the questions asked and the answers received are worth reading and contain more useful and pertinent information than the "mediatization" article. Here is the link:

Mobile Technology Survey Project.

As an aside, I noticed that this author, with her long and profound experience, is much more attuned to the multinational, multicultural and multilingual composition of the Camino pilgrim population, and in particular to the segment of Spanish pilgrims who represent after all the majority, than many others who attempt surveys to write about them.

Thanks for this link.

Phenomonenological points:

Pondering the degree to which “the phone” is a “feminine” communication tool, frequently disparaged as something women spend too much time on, underpaid from the outset as “women’s work” associated with switchboard operators… And yet, the tool has been indispensable in the work of receiving crucial messages in a timely manner.

It’s just so *easy* to stick with the disparagement of the “phone” as something vapid, though. I would encourage any pilgrim to examine why they might get such a kick out of judging others as vapid or lacking in spiritual integrity because they are not “properly disconnected”.

Asking how the phone has changed our ability to connect is a fair question, from a technological and efficiency perspective. But when we move it into phenomenological territory, I think there is an argument to be made that “the phone” is just being used as a convenient flashpoint for taking out aggression on others who have done us no harm by staying connected to their home-bases. What motivates the desire? Is it maybe jealousy that some people have people who miss them and worry about them?

Technical Points:

I am struck by how many more of us have a Swiss Army Knife phone now. The smart phone really is not used so often as a *phone* anymore. Mine, for example, is a hotspot when I am in the bush so that I can connect my laptop and continue teaching duties after lecture season ends and before mosquito season begins. But what else is my phone?

It is a camera, and so when I am on any excursion, it is always within reach so that I can grab photos. I’m a terrible photographer, but with the “phone” I have come to take really lovely outdoor photos that I cherish.

It is a reservoir for copies of all my safety documents (passport, health card, insurance information).

It is where my travel tickets are often held now — for train tickets, bus and plane boarding passes.

It holds my guide books (

Wise Pilgrim) and, thus, my live maps as well.

These tools are, I think, common uses for pilgrims of all stripes now. Less than 6 oz for all that. In my side pocket.

Added bonuses:

It has a tracker beacon that connects me to my various family members. Tracking my moving dot gives great comfort to my mother and son when I am on camino.

My watch, connected to my phone, tells me if my mother has not risen from her nap, which means I can alert a proxy care-giver to go make sure she’s not in an insulin shock (and deliver her a glucose treatment if she is).

There are so many tools on phones now that are so much more sophisticated than when Frey wrote up this survey.

A 2022 survey would have to take into account that the average device is not at all a mere phone anymore.

On our 2018 camino, Spouse and I added WhatsApp because our son uses it, and it works on his computer even if he breaks his phone or loses it. I still have our conversation thread from 2018, and I still enjoy looking at it because it cracks me up. When we were outrunning the Sarria crush and did Arzua to SdC in one day so that we’d not have trouble getting a bed in O’Porrino, he sent us a GIF of Sean Connery as James Bond, driving furiously and erratically to get away from the villains in a car chase in “Dr. No”.

Methodological and Interpretive Points:

“Connection” and “Disconnection” are poorly defined operational definitions in all these moral evaluations of pilgrimage — it seeps into Frey, and it certainly shapes the answers pilgrims give about the “quality of pilgrimage”. Are we “over connected” because of our devices? Are we actually more stressed than humans have ever been before? Really? The historical presentism of such assertions and their ubiquity leaves me rather agog.

At the end of the day, I refuse to evaluate whether another pilgrim/walker/holiday maker is having a proper experience by any means. The infamous Bus Tour of Europe is not for me; I’m glad I don’t go on “packages” as my in-laws do, but people enjoy such things, just as they enjoy doing the camino according to the Brierely recipe. Not for me…. Not an indicator that they are lessor beings.

The only person I think may not have learned something of value on a camino is the one who feels entitled by their experience to judge all others as somehow “doing it wrong”.

People do the best they can within the confines of their circumstances.

Conceptual Points:

I find questions about “true camino experiences” or notions of authenticity to be banal in the extreme.

Of course “the experience” has changed over 1000+ years. But did people ever have a singular experience? That is doubtful. The present assertion that *how you arrive* at Santiago — that the journey is more important than the destination would not only confuse but would also insult the early Catholic Church. People walked because that was almost the only option. Donkeys and horses are complications on a long journey. Walking 5K into SdC from one’s 17th C abode in an outlying town was a miracle of birth, not to be sneered at but to be envied. To live in the lee of any important cathedral was a blessing. The walkers were merely aiming to get close to the blessings and the power of the church for a little while, and perhaps to carry that mystical power with them for a while.

Much of the popular view of current pilgrimage seems to me to be a hodge-podge of radical individualism, self-help, yoga distilled via self-help, and so forth. It would mystify the church that created the anchoring points for things like the camino, the Via Francigena, and so forth. That’s fine, but it is worth considering just how far afield current assertions are about “traditional“ attitudes to making the walk are.

Victor Turner has some exceptional anthropological work on the symbolic world of European pilgrimage.

Robert Scott also — medical sociologist who explains the relationship of pilgrimage to healing, to “miracle cures” and to the rise of the hospital.

General medieval historians provide insights to the circumstances for the rise of pilgrimage; Dorsey Armstrong is a good source for the broad survey…

There is no single, pan-historical, authentic way to be or to undertake pilgrimage. Like the rest of human life, it changes constantly. What it delivers to any one of us is as variable as we are, and as constrained as the context of the path that the road literally follows. It is both predictable and malleable. Technologies have always been part of the road (see the wonderful thread about Roman architecture and road building and the speed of message delivery that the roads made possible!).

I think I we ought all to stop worrying about how other people do their pilgrimages, or experience them. And at the same time, we ought to refrain from asserting that our own ways ought never to be inconvenienced by the presence of others.

www.mdpi.com

www.mdpi.com