- Time of past OR future Camino

- Many, various, and continuing.

This is an address delivered at the 2017 gathering of American Pilgrims on the Camino (APOC) in Atlanta, Ga. last weekend, on "the future of hospitality on the camino." It ruffled a few feathers, which is always good. I post it here by popular demand:

The future of hospitality on the Camino. Rebekah Scott

I am not a prophet. I can’t tell you what the future holds, and anyone who says he can has pants on fire.

I can tell you, though, about trends, and about what I’ve seen on the ground on the Way over a period of more than 20 years. I am as trustworthy a guide as anybody. So,

We stand here together in the present, at a crossroads.

We all have come here from a vast and varied place called the Past, a country that for most of us included at least one long, hard voyage along the Camino de Santiago.

Most of us are weathered veterans. Out there you walked until you were ready to drop. When you needed it most, you found a place with a bed and maybe a beer and maybe a smiling face: a welcome. A Camino Welcome. Stop there. Look around at the place your mind has chosen to illustrate “Camino Hospitality.” Where are you? Your subconscious chose this particular place, of all the many places you stopped and stayed along the Way. So set down a marker here.

Continue on with me.

Into the here and now. We are gathered here today in Atlanta, far away from the physical Camino, but immersed in a virtual Way that’s made up of people much like us.

From our comfortable chairs we look today into an entirely new country, an unexplored territory, wild and woolly and probably scary. We’re looking at The Future.

My name is Rebekah Scott, an American pilgrim from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My Camino Past goes back to 1993, when I first stepped onto the Camino de Santiago. I went there as a travel journalist, an honored guest of the Tourist Office of Spain – it was a marketing ploy on their part. They wanted our articles in North American newspapers and magazines to lure well-heeled tourists to this “adventure destination.” There wasn’t a whole lot to see on the Camino in those days, hospitality and accommodation-wise. We visited “refugios,” – abandoned schools, convent dorms, and remodeled garages where pilgrims could stay for little or nothing.

They were usually rather dirty and cold -- the refugios as well as the people inside. Pilgrims cooked their own meals, or ate from cans and packages they bought at supermarkets and carried with them. Menu del Dias were only on offer in big towns. Pilgrims walked in huge mountain-hiking boots, or sneakers and jeans and t-shirts. They carried their things in school bags and Army backpacks. There was no wifi. No one even had a mobile phone. It was 24 years ago, but it was the Stone Age of the modern camino. About 26,000 people made the trip, and that was a special holy year.

It was scruffy and ancient and full of character. I fell in love.

When I think of that first taste of the Camino, and I think of hospitality, I think of a stranger who stepped out onto the road as we passed through a little Leonese village. He greeted us, offered us a glass of his home-made wine. There was no price tag. He did it just because.

I met Jesus Jato, a mad man with a ramshackle albergue growing up inside his burned-out greenhouse in Villafranca de Bierzo. He needed a haircut. My coffee mug was unwashed. The showers were garden hoses stapled to the wall, with cold water only. The place was more like a refugee camp than an albergue, but the hollow-eyed young Spanish pilgrims bunking there did not complain. This was a pilgrimage, they told me. It was all about roughing it, doing without, crucifying the flesh.

I stayed and talked – as much as I could – to the pilgrims and Jato and Jato’s wife. I took tons of notes, and photos. They invited me to stay for dinner – lentils and bread, wine and cheese. There were six of us there that night. When I asked what I owed, Jato pointed at the donation box. “Whatever you want to pay,” he said.

I said goodbye. “We’re just getting started, you know,” he told me. “I’ll see you again.”

I am not a prophet, but Jesus Jato is. He could see the future. He saw mine.

I came back alright. In 2001 I finally walked the whole thing. I knew then I needed to change my life, become a part of this phenomenon.

I became a volunteer hospitalero in 2003, trained at an APOC/Canadian Company joint gathering in Toronto. I went back to the Camino time after time and served two-week stints at pilgrim shelters all over the caminos. I learned the caminos from the other side of the desk.

In 2006 I emigrated altogether. My husband and I bought an old farm in the middle of the camino, and opened the doors to pilgrims who need a place to stay – a little like mad old Jato, but on a much smaller and more private scale. In the years since I’ve written guides to alternative trails, trained new volunteers for the Spanish hospitalero voluntario program, wrote a training program now in use in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. I wrote a camino novel, even.

We have been hosting pilgrims on the Camino for more than a decade now, and are as integrated into the Spanish pilgrimage infrastructure as two foreign hermits can be.

SO… Now that we have my past out of the way, We all can move forward.

Which requires a quick look at the Present.

Nowadays I am hospitality coordinator for the Fraternidad Internacional del Camino de Santiago, a camino activist group founded two years ago by some of the latter-day camino founders, including Jesus Jato and George Greenia.

I oversee the volunteers at two pilgrim albergues still dedicated to donations-based accommodation. We do good, on a donation basis, because that’s our franchise. Free-will accommodation is a major part of what makes the Camino unique. We have an overwhelmingly international group of volunteers…

Every single year is a record-breaker on the camino de Santiago, pilgrim-numbers wise. More than 270,000 people walked the camino last year, people from 160 countries. They walk all the year around, right through December and January – months when we used to rarely see anyone on the Road. The makeup the of pilgrims has changed greatly too. There are just as many women walking as men. Spaniards are now only 47% of the pilgrims. It’s not just a European phenomenon, either: the numbers of Americans, Russians, Chinese, and Korean pilgrims have increased more than 200 percent since 2011. In the summertime we open the church in Moratinos, our little town on the Meseta. Last year we saw our first pilgrims from Burundi, Mauritania, and Cabo Verde. People who can afford to fly from around the world are not poor.

The number of Camino routes has increased greatly as old routes are rediscovered and new routes are invented. Ten years ago, the paint was just drying on the Camino Portuguese waymarkers – now it’s the second-most traveled trail to Santiago. Another interesting change is the drop in the number of cyclists on the Camino. In the 1990’s, 21 percent of pilgrims rode bikes. In 2015, only 10 percent did it that way.

On the Camino Frances alone, there are now more than 400 places for pilgrims to spend a night. There are 1,200 places to stop and eat. I am not a statistician, but I can blithely say the number of pilgrim-targeted businesses on the camino Frances has quadrupled in the ten years I have lived on the trail. The increasing number of pilgrims has attracted the attention of the marketers, the entrepreneurs, the Capitalists.

And hereby hangs a conflict.

I will try to give a nice, value-free, balanced view, but I will warn you going into this Future that I am an idealist, and a Christian. I am judgmental. I consider the Camino de Santiago a sacred place, a monument that merits our respect and preservation.

You can travel the Camino de Santiago without being a pilgrim. It’s a beautiful place with a bargain-priced infrastructure and 3G and a fun vibe. You might have a great time, but you won’t have the same deep experience as many of the people you see out the bus window. You might have to come back again. “Today’s tourist is tomorrow’s pilgrim,” after all.

But this is a pilgrimage trail. If you are not a pilgrim, you are not fully invested in this experience. You should not expect to be treated as a pilgrim.

Pilgrimage is a spiritual journey, a discipline, a process of stripping away everything unneeded for basic survival. The person who seriously wants a pilgrim experience will go as minimalist as he can. He’ll leave behind technology and comforts and distractions. He’ll throw himself onto the mercy of the trail itself, just as pilgrims have done for a thousand years. He’ll depend on the kindness of others to provide him with a place to sleep, something to eat and drink, without presumption or entitlement. Pilgrims who take that kind of risk find themselves borne on a wave of providence. It’s a radical thing to do. It’s crazy, it’s scary. It’s kinda miraculous. And it still works.

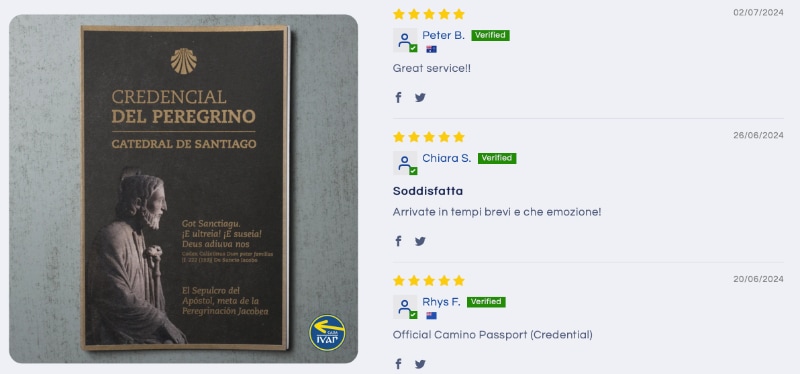

This radical minimalism flies right into the face of our ingrained consumerism, and the travel industry -- the people who are selling a safe, clean, dreamy Camino. Check out any FaceBook Camino page. There you’ll see the hotel and transport and “adventure destination” marketers; the folks who say that “real pilgrims” buy this or wear that or stay at this place, who tell you this trail, soap, backpack, sock, scarf, diary, app, bandage, credential, or guidebook may lead to a blister-free, painless, Camino Nirvana.

We Americans eat it up. We are born and raised to get and spend. We are born Consumers. “Value for Money” is the prime objective, “convenience” is ours by birthright. We live by “the customer is always right,” as well as “I spent good money on this, and I expect a return on my investment…” In recent years entrepreneurs along the trail have jumped up to meet our demands for clean, charming, and predictable accommodation, offered at a price we well-funded Westerners are prepared to pay.

So…

We find the camino. We hear the call. We being born consumers, our first impulse is to Shop.

Second impulse? Find out everything possible in advance, read books and websites, and plot our course down to the last scripture verse and well-rated coffee bar.

We want it all, on our own terms.

We want an adventure, but we don’t like surprises.

We want all the enlightenment and excitement of a tough hike across a new land, but we want it safe, hygienic, and predictable, served with a smile at less than 20 Euros.

We want to stay at the albergue everyone else rated best, take the best photos of the local food and wine, write the blog everyone will read. And dammit, We want to look pretty and put-together at the end of the day!

Comfortable consumer Capitalism, and the primal simplicity of the Camino, (and pilgrimage,) are deeply at odds with one another.

And this is why the Camino de Santiago, when we finally get it, blows our American minds.

We are consumers, walking into a world where Less is More.

Where everyone is just as good or important or respectable as everyone else on the trail.

Where uncertainty and risk and flexibility… and even sacrifice and suffering (O my!) are built-in parts of the experience, maybe even requirements for a truly successful outcome.

In my opinion, North Americans are perfect pilgrim material. We are full of demands, expectations, dreams and plans and fears and derring-do. We carry hundreds of dollars’ worth of new equipment, as well as other great burdens. We have a lot to lose, bringing our complicated selves to such a simple, demanding place.

And on the Camino we find out quickly that our Stuff won’t save us. It only makes us suffer.

We find a place to sleep, with or without reservations. We find out how little stuff we need to get by. We find that no one cares what our hair looks like. We find people who care for us, no matter how we look or feel or act or even smell.

We find places to stay where we’re not viewed as walking wallets, where we are treated as friends, made welcome, offered comfort and simple food and care by people who volunteer to come and do this work.

Camino magic happens to us. It’s another world, another economy. An economy based on giving, not getting.

Remember that place that stands out in your mind, that albergue where you felt so welcome? Bring that back to your mind. Think about what it was that made it so special.

What made them stand out? Was it value for money? The number of power outlets? The swimming pool? The sparkling clean showers? The dinner, wine, laundry service? The massage?

Or was it the welcome? The hospitaleros?

These are small, often volunteer-run places. Often they are donativos, or they recently were.

Of more than 400 places to stay on the Camino Frances, 30 are still donativo. Many that once were donation-based still charge 6 euro or less, just to keep themselves alive on a trail plagued by freeloaders who won’t pay anything unless it is required.

Pilgrims traveling without resources, the people who albergues were originally aimed-at, are now back to sleeping in the street, as the low-cost beds are now full of, well… who are these pilgrims?

The donativo ideal is almost dead on the Camino Frances. Beloved, old-school albergues like Santo Domingo de la Calzada, Las Carbajales in Leon, and the Benedictinas in Sahagun all have given up on the donativo/volunteer model in the past few years, simply overwhelmed by the demand of something-for-nothing accommodation.

If pilgrim numbers continue to grow, or if they even level off at current levels, donativos will disappear, victims of high overhead costs, pilgrims who leave nothing in the box, as well as new provincial laws written to favor hoteliers. Plenty of people will continue to walk, but the Camino gold rush may really succeed in killing the goose that lays the golden eggs.

Last summer, up at Foncebadon, I heard some handsome American pilgrims discussing that former ghost town brought back to life in the past 20 years.

“This place is great! We did this. It’s our pilgrim money that brought this here,” one of them said. “Someone ought to invest in some nice paving, signage, marketing. Some safety measures, maybe. Imagine what some decent branding could do up here.”

“Yeah, clean this place up and you could make some good money. This could be really cute.”

Yeah, just imagine. Scruffy Foncebadon, and Tosantos, and Calzadilla de los Hermanillos… scrubbed down and paved and Disney-fied and cute.

I almost went Full Prophet on those guys, but I contained myself. They are consumers. They obviously had not walked up that mountain. They don’t know anything different. Unfortunately, many of the people who want to plasticize the Camino are thinking the very same way. People who see beautiful, unique things as opportunities to make money… or even well-meaning people who see something scruffy or rural or strange and feel compelled to “improve” it.

FICS is dedicated to exploring and dealing with this phenomenon. We have our work cut out for us. We work hard and make lots of noise, but we don’t have a lot of illusions.

Eventually, large parts of the camino will be as Disney-fied as the final 100 kilometers from Sarria, and the overbuilding and paving and improvements will render the Camino accessible and do-able to anyone with money. Families who open spare rooms to pilgrims will be outlawed, minimum charges will be levied on all accommodations, and Compostela certificates will be issued by vending machines or print-your-own apps.

Once the Camino is fully commodified, numbers will peak even higher than we see now. People in search of easy grace and instant karma will flood in and have a whale of a time. Prices will rise, accommodations will become more private and luxurious as the low-cost/bunkhouse aesthetic is swept away in a flood of profit-making tourism. Groups like APOC will close down their hospitalero training programs, because hospitality will be turned over to the professionals. The crazy old prophets and healers will be distant memories – cardboard cutouts standing outside souvenir shops.

The camino as it is today is not sustainable. A corporate camino, with all its good-will hospitality stripped away, will be even less so. We will eliminate the ver simplicity that make the camino unique.

Maybe the great blow will come in a flash. Tourists are notoriously fickle and fearful. A single serious terror attack would strip out a good 50 percent of that year’s pilgrim numbers, and continue to affect the phenomenon for years after.

Maybe it will be a slow slide. Eventually, everyone who is anyone will have done the camino. It will fall out of fashion, and numbers will slowly drop off. Like Yogi Berra said, “Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded.” The expensive hotels will die first, and slowly the rest will fall away, too, over many years. The pavement will crumble. Trees will grow tall and drop their leaves on the path, year after year. What’s cool today will be history in just a few years. Our grandchildren will look at our pilgrimages, and maybe they’ll laugh a little at our silly trendy-ness, and wonder why we bothered fighting so hard for a nasty old footpath. The plastic camino will die, yet again the victim of changing times. I believe that within 70 years of today, the camino will go back to sleep.

But it will not die.

Farther, deeper into the future, a few people will read our old accounts, and feel the pull of that old road. A few of them will put on what passes for a pack in those future days. They’ll find a handy starting-place, and they’ll start walking.

Somewhere along the Way, a resident will meet the traveler, and invite him in for a glass of wine, or a meal. He’ll offer a bed in the spare room, or the barn. He won’t ask for money. The pilgrim won’t offer to pay. Once again, as through the ages, the pilgrimage will not be a transaction. It will be a work of grace.

The bartender will give the rain-soaked wanderer an extra cup of broth, because his grandma used to do that for pilgrims, back in the day. There won’t be a hundred other pilgrims pushing in the door, so he’ll be able to talk to the stranger, hear his story.

On Sunday morning, if he’s lucky, the pilgrim can follow the church bell into a parish church, and be welcomed as a special, lucky guest at the neighborhood Mass.

He’ll sleep wherever he can find a bed. He’ll probably pay, and probably be ripped-off now and then. He’ll sleep outdoors some times. He’ll be rained-on, sunburned, bed-bugged, and blistered. He will sing out loud, and laugh at his own jokes, and learn difficult truths about himself.

And eventually he will reach Santiago de Compostela, where the cathedral will, perhaps, award him with a Compostela certificate. Or maybe they’ll have gotten out of the souvenir business by then.

This is my prophecy:

The camino has survived all kinds of abuses over hundreds of years – plagues, wars, famines, Renaissances, Reformations, Fascists and Republics, even the Spanish Inquisition! It will survive Consumerism, too. We humans crucify the very thing that makes us most alive. It dies, and is buried. But on the third day, it rises again.

The Camino will survive us. The pilgrims will not stop walking, and the trail will not fail to rise up and welcome them, until we utterly destroy the Way. Or we destroy our selves.

The future of hospitality on the Camino. Rebekah Scott

I am not a prophet. I can’t tell you what the future holds, and anyone who says he can has pants on fire.

I can tell you, though, about trends, and about what I’ve seen on the ground on the Way over a period of more than 20 years. I am as trustworthy a guide as anybody. So,

We stand here together in the present, at a crossroads.

We all have come here from a vast and varied place called the Past, a country that for most of us included at least one long, hard voyage along the Camino de Santiago.

Most of us are weathered veterans. Out there you walked until you were ready to drop. When you needed it most, you found a place with a bed and maybe a beer and maybe a smiling face: a welcome. A Camino Welcome. Stop there. Look around at the place your mind has chosen to illustrate “Camino Hospitality.” Where are you? Your subconscious chose this particular place, of all the many places you stopped and stayed along the Way. So set down a marker here.

Continue on with me.

Into the here and now. We are gathered here today in Atlanta, far away from the physical Camino, but immersed in a virtual Way that’s made up of people much like us.

From our comfortable chairs we look today into an entirely new country, an unexplored territory, wild and woolly and probably scary. We’re looking at The Future.

My name is Rebekah Scott, an American pilgrim from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My Camino Past goes back to 1993, when I first stepped onto the Camino de Santiago. I went there as a travel journalist, an honored guest of the Tourist Office of Spain – it was a marketing ploy on their part. They wanted our articles in North American newspapers and magazines to lure well-heeled tourists to this “adventure destination.” There wasn’t a whole lot to see on the Camino in those days, hospitality and accommodation-wise. We visited “refugios,” – abandoned schools, convent dorms, and remodeled garages where pilgrims could stay for little or nothing.

They were usually rather dirty and cold -- the refugios as well as the people inside. Pilgrims cooked their own meals, or ate from cans and packages they bought at supermarkets and carried with them. Menu del Dias were only on offer in big towns. Pilgrims walked in huge mountain-hiking boots, or sneakers and jeans and t-shirts. They carried their things in school bags and Army backpacks. There was no wifi. No one even had a mobile phone. It was 24 years ago, but it was the Stone Age of the modern camino. About 26,000 people made the trip, and that was a special holy year.

It was scruffy and ancient and full of character. I fell in love.

When I think of that first taste of the Camino, and I think of hospitality, I think of a stranger who stepped out onto the road as we passed through a little Leonese village. He greeted us, offered us a glass of his home-made wine. There was no price tag. He did it just because.

I met Jesus Jato, a mad man with a ramshackle albergue growing up inside his burned-out greenhouse in Villafranca de Bierzo. He needed a haircut. My coffee mug was unwashed. The showers were garden hoses stapled to the wall, with cold water only. The place was more like a refugee camp than an albergue, but the hollow-eyed young Spanish pilgrims bunking there did not complain. This was a pilgrimage, they told me. It was all about roughing it, doing without, crucifying the flesh.

I stayed and talked – as much as I could – to the pilgrims and Jato and Jato’s wife. I took tons of notes, and photos. They invited me to stay for dinner – lentils and bread, wine and cheese. There were six of us there that night. When I asked what I owed, Jato pointed at the donation box. “Whatever you want to pay,” he said.

I said goodbye. “We’re just getting started, you know,” he told me. “I’ll see you again.”

I am not a prophet, but Jesus Jato is. He could see the future. He saw mine.

I came back alright. In 2001 I finally walked the whole thing. I knew then I needed to change my life, become a part of this phenomenon.

I became a volunteer hospitalero in 2003, trained at an APOC/Canadian Company joint gathering in Toronto. I went back to the Camino time after time and served two-week stints at pilgrim shelters all over the caminos. I learned the caminos from the other side of the desk.

In 2006 I emigrated altogether. My husband and I bought an old farm in the middle of the camino, and opened the doors to pilgrims who need a place to stay – a little like mad old Jato, but on a much smaller and more private scale. In the years since I’ve written guides to alternative trails, trained new volunteers for the Spanish hospitalero voluntario program, wrote a training program now in use in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. I wrote a camino novel, even.

We have been hosting pilgrims on the Camino for more than a decade now, and are as integrated into the Spanish pilgrimage infrastructure as two foreign hermits can be.

SO… Now that we have my past out of the way, We all can move forward.

Which requires a quick look at the Present.

Nowadays I am hospitality coordinator for the Fraternidad Internacional del Camino de Santiago, a camino activist group founded two years ago by some of the latter-day camino founders, including Jesus Jato and George Greenia.

I oversee the volunteers at two pilgrim albergues still dedicated to donations-based accommodation. We do good, on a donation basis, because that’s our franchise. Free-will accommodation is a major part of what makes the Camino unique. We have an overwhelmingly international group of volunteers…

Every single year is a record-breaker on the camino de Santiago, pilgrim-numbers wise. More than 270,000 people walked the camino last year, people from 160 countries. They walk all the year around, right through December and January – months when we used to rarely see anyone on the Road. The makeup the of pilgrims has changed greatly too. There are just as many women walking as men. Spaniards are now only 47% of the pilgrims. It’s not just a European phenomenon, either: the numbers of Americans, Russians, Chinese, and Korean pilgrims have increased more than 200 percent since 2011. In the summertime we open the church in Moratinos, our little town on the Meseta. Last year we saw our first pilgrims from Burundi, Mauritania, and Cabo Verde. People who can afford to fly from around the world are not poor.

The number of Camino routes has increased greatly as old routes are rediscovered and new routes are invented. Ten years ago, the paint was just drying on the Camino Portuguese waymarkers – now it’s the second-most traveled trail to Santiago. Another interesting change is the drop in the number of cyclists on the Camino. In the 1990’s, 21 percent of pilgrims rode bikes. In 2015, only 10 percent did it that way.

On the Camino Frances alone, there are now more than 400 places for pilgrims to spend a night. There are 1,200 places to stop and eat. I am not a statistician, but I can blithely say the number of pilgrim-targeted businesses on the camino Frances has quadrupled in the ten years I have lived on the trail. The increasing number of pilgrims has attracted the attention of the marketers, the entrepreneurs, the Capitalists.

And hereby hangs a conflict.

I will try to give a nice, value-free, balanced view, but I will warn you going into this Future that I am an idealist, and a Christian. I am judgmental. I consider the Camino de Santiago a sacred place, a monument that merits our respect and preservation.

You can travel the Camino de Santiago without being a pilgrim. It’s a beautiful place with a bargain-priced infrastructure and 3G and a fun vibe. You might have a great time, but you won’t have the same deep experience as many of the people you see out the bus window. You might have to come back again. “Today’s tourist is tomorrow’s pilgrim,” after all.

But this is a pilgrimage trail. If you are not a pilgrim, you are not fully invested in this experience. You should not expect to be treated as a pilgrim.

Pilgrimage is a spiritual journey, a discipline, a process of stripping away everything unneeded for basic survival. The person who seriously wants a pilgrim experience will go as minimalist as he can. He’ll leave behind technology and comforts and distractions. He’ll throw himself onto the mercy of the trail itself, just as pilgrims have done for a thousand years. He’ll depend on the kindness of others to provide him with a place to sleep, something to eat and drink, without presumption or entitlement. Pilgrims who take that kind of risk find themselves borne on a wave of providence. It’s a radical thing to do. It’s crazy, it’s scary. It’s kinda miraculous. And it still works.

This radical minimalism flies right into the face of our ingrained consumerism, and the travel industry -- the people who are selling a safe, clean, dreamy Camino. Check out any FaceBook Camino page. There you’ll see the hotel and transport and “adventure destination” marketers; the folks who say that “real pilgrims” buy this or wear that or stay at this place, who tell you this trail, soap, backpack, sock, scarf, diary, app, bandage, credential, or guidebook may lead to a blister-free, painless, Camino Nirvana.

We Americans eat it up. We are born and raised to get and spend. We are born Consumers. “Value for Money” is the prime objective, “convenience” is ours by birthright. We live by “the customer is always right,” as well as “I spent good money on this, and I expect a return on my investment…” In recent years entrepreneurs along the trail have jumped up to meet our demands for clean, charming, and predictable accommodation, offered at a price we well-funded Westerners are prepared to pay.

So…

We find the camino. We hear the call. We being born consumers, our first impulse is to Shop.

Second impulse? Find out everything possible in advance, read books and websites, and plot our course down to the last scripture verse and well-rated coffee bar.

We want it all, on our own terms.

We want an adventure, but we don’t like surprises.

We want all the enlightenment and excitement of a tough hike across a new land, but we want it safe, hygienic, and predictable, served with a smile at less than 20 Euros.

We want to stay at the albergue everyone else rated best, take the best photos of the local food and wine, write the blog everyone will read. And dammit, We want to look pretty and put-together at the end of the day!

Comfortable consumer Capitalism, and the primal simplicity of the Camino, (and pilgrimage,) are deeply at odds with one another.

And this is why the Camino de Santiago, when we finally get it, blows our American minds.

We are consumers, walking into a world where Less is More.

Where everyone is just as good or important or respectable as everyone else on the trail.

Where uncertainty and risk and flexibility… and even sacrifice and suffering (O my!) are built-in parts of the experience, maybe even requirements for a truly successful outcome.

In my opinion, North Americans are perfect pilgrim material. We are full of demands, expectations, dreams and plans and fears and derring-do. We carry hundreds of dollars’ worth of new equipment, as well as other great burdens. We have a lot to lose, bringing our complicated selves to such a simple, demanding place.

And on the Camino we find out quickly that our Stuff won’t save us. It only makes us suffer.

We find a place to sleep, with or without reservations. We find out how little stuff we need to get by. We find that no one cares what our hair looks like. We find people who care for us, no matter how we look or feel or act or even smell.

We find places to stay where we’re not viewed as walking wallets, where we are treated as friends, made welcome, offered comfort and simple food and care by people who volunteer to come and do this work.

Camino magic happens to us. It’s another world, another economy. An economy based on giving, not getting.

Remember that place that stands out in your mind, that albergue where you felt so welcome? Bring that back to your mind. Think about what it was that made it so special.

What made them stand out? Was it value for money? The number of power outlets? The swimming pool? The sparkling clean showers? The dinner, wine, laundry service? The massage?

Or was it the welcome? The hospitaleros?

These are small, often volunteer-run places. Often they are donativos, or they recently were.

Of more than 400 places to stay on the Camino Frances, 30 are still donativo. Many that once were donation-based still charge 6 euro or less, just to keep themselves alive on a trail plagued by freeloaders who won’t pay anything unless it is required.

Pilgrims traveling without resources, the people who albergues were originally aimed-at, are now back to sleeping in the street, as the low-cost beds are now full of, well… who are these pilgrims?

The donativo ideal is almost dead on the Camino Frances. Beloved, old-school albergues like Santo Domingo de la Calzada, Las Carbajales in Leon, and the Benedictinas in Sahagun all have given up on the donativo/volunteer model in the past few years, simply overwhelmed by the demand of something-for-nothing accommodation.

If pilgrim numbers continue to grow, or if they even level off at current levels, donativos will disappear, victims of high overhead costs, pilgrims who leave nothing in the box, as well as new provincial laws written to favor hoteliers. Plenty of people will continue to walk, but the Camino gold rush may really succeed in killing the goose that lays the golden eggs.

Last summer, up at Foncebadon, I heard some handsome American pilgrims discussing that former ghost town brought back to life in the past 20 years.

“This place is great! We did this. It’s our pilgrim money that brought this here,” one of them said. “Someone ought to invest in some nice paving, signage, marketing. Some safety measures, maybe. Imagine what some decent branding could do up here.”

“Yeah, clean this place up and you could make some good money. This could be really cute.”

Yeah, just imagine. Scruffy Foncebadon, and Tosantos, and Calzadilla de los Hermanillos… scrubbed down and paved and Disney-fied and cute.

I almost went Full Prophet on those guys, but I contained myself. They are consumers. They obviously had not walked up that mountain. They don’t know anything different. Unfortunately, many of the people who want to plasticize the Camino are thinking the very same way. People who see beautiful, unique things as opportunities to make money… or even well-meaning people who see something scruffy or rural or strange and feel compelled to “improve” it.

FICS is dedicated to exploring and dealing with this phenomenon. We have our work cut out for us. We work hard and make lots of noise, but we don’t have a lot of illusions.

Eventually, large parts of the camino will be as Disney-fied as the final 100 kilometers from Sarria, and the overbuilding and paving and improvements will render the Camino accessible and do-able to anyone with money. Families who open spare rooms to pilgrims will be outlawed, minimum charges will be levied on all accommodations, and Compostela certificates will be issued by vending machines or print-your-own apps.

Once the Camino is fully commodified, numbers will peak even higher than we see now. People in search of easy grace and instant karma will flood in and have a whale of a time. Prices will rise, accommodations will become more private and luxurious as the low-cost/bunkhouse aesthetic is swept away in a flood of profit-making tourism. Groups like APOC will close down their hospitalero training programs, because hospitality will be turned over to the professionals. The crazy old prophets and healers will be distant memories – cardboard cutouts standing outside souvenir shops.

The camino as it is today is not sustainable. A corporate camino, with all its good-will hospitality stripped away, will be even less so. We will eliminate the ver simplicity that make the camino unique.

Maybe the great blow will come in a flash. Tourists are notoriously fickle and fearful. A single serious terror attack would strip out a good 50 percent of that year’s pilgrim numbers, and continue to affect the phenomenon for years after.

Maybe it will be a slow slide. Eventually, everyone who is anyone will have done the camino. It will fall out of fashion, and numbers will slowly drop off. Like Yogi Berra said, “Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded.” The expensive hotels will die first, and slowly the rest will fall away, too, over many years. The pavement will crumble. Trees will grow tall and drop their leaves on the path, year after year. What’s cool today will be history in just a few years. Our grandchildren will look at our pilgrimages, and maybe they’ll laugh a little at our silly trendy-ness, and wonder why we bothered fighting so hard for a nasty old footpath. The plastic camino will die, yet again the victim of changing times. I believe that within 70 years of today, the camino will go back to sleep.

But it will not die.

Farther, deeper into the future, a few people will read our old accounts, and feel the pull of that old road. A few of them will put on what passes for a pack in those future days. They’ll find a handy starting-place, and they’ll start walking.

Somewhere along the Way, a resident will meet the traveler, and invite him in for a glass of wine, or a meal. He’ll offer a bed in the spare room, or the barn. He won’t ask for money. The pilgrim won’t offer to pay. Once again, as through the ages, the pilgrimage will not be a transaction. It will be a work of grace.

The bartender will give the rain-soaked wanderer an extra cup of broth, because his grandma used to do that for pilgrims, back in the day. There won’t be a hundred other pilgrims pushing in the door, so he’ll be able to talk to the stranger, hear his story.

On Sunday morning, if he’s lucky, the pilgrim can follow the church bell into a parish church, and be welcomed as a special, lucky guest at the neighborhood Mass.

He’ll sleep wherever he can find a bed. He’ll probably pay, and probably be ripped-off now and then. He’ll sleep outdoors some times. He’ll be rained-on, sunburned, bed-bugged, and blistered. He will sing out loud, and laugh at his own jokes, and learn difficult truths about himself.

And eventually he will reach Santiago de Compostela, where the cathedral will, perhaps, award him with a Compostela certificate. Or maybe they’ll have gotten out of the souvenir business by then.

This is my prophecy:

The camino has survived all kinds of abuses over hundreds of years – plagues, wars, famines, Renaissances, Reformations, Fascists and Republics, even the Spanish Inquisition! It will survive Consumerism, too. We humans crucify the very thing that makes us most alive. It dies, and is buried. But on the third day, it rises again.

The Camino will survive us. The pilgrims will not stop walking, and the trail will not fail to rise up and welcome them, until we utterly destroy the Way. Or we destroy our selves.