Gerard Murdoch

Active Member

- Time of past OR future Camino

- Ponferrada - Santiago (2013)

Porto to Santiago (2015)

Lugo to Finisterre (2017)

Porto Coastal (2019)

I would like to share an article from the Whithorn Trust, Who is involved with the Whithorn Way and St Ninian of Scotland https://www.whithorn.com/walk-the-whithorn-way/

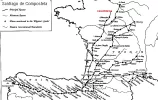

Today, a note on one of the further flung Ninian connections, demonstrating the devotion of expat Scots to their Saint who had acquired national standing by the 15th and 16th Centuries, and a bit more on the history of hot baths. We've spoken in a recent post about the preparation required for pilgrimage and the cost particularly of the longest and most arduous journeys, of which travel across the Pyrenees towards Compostela was and remains one of the great mediaeval pilgrim journeys. The merit of the longer journey on foot, rather than taking the shorter (more costly) sea route, was that spiritual benefits could be accrued on the way by visiting a multiplicity of other shrines, which are mentioned in the famous so-called Pilgrim's Guide, which forms the final book of the "Jacobus", a compilation of lives of Saint James of Compostela. The final book of the Codex Calixtinus ( its other name, after the Pope) describes the pilgrimage, with a chapter on roads through France, which meet at Puente la Reina. En route, accommodation was available in wayside hospitals, including that at Dax, just north of the Iberian frontier. Pilgrims from Scotland, having come on this long journey, must have felt at home, when they found the hospital here had, according to David Ditchburn, been either built or repaired by an expatriate pious and apparently patriotic Scot in the sixteenth century and it must surely have been an especial attraction that they could collect an indulgence by contributing to the hospital’s maintenance on the feast days of the Virgin, and Scotland's national saints, St Andrew and St Ninian (in this context of course, "hospital" has the mediaeval meaning derived from the Latin word hospitalis, meaning accommodating hospites, or guests - any persons who needed shelter). Dax (Aquae, Acqs, d'Acqs)at the time was thronged with pilgrims en route for Compostela, and it was richly supplied with jewellers' shops to make settings for the seashells which were symbols of the pilgrimage. Dax is still famed for its thermal water and the healing mud from the river Adour, which were believed to treat rheumatic and phlebological ailments. The “Fontaine Chaude” is a mineral spring erected on the ruins of the Roman bath. Today, on the main street, a marble trough has a row of Roman bronze lion heads with open mouths, and above it the columns of the Roman bath. The miracles of Dax began before the arrival of pilgrims, when, according to local legend, a Roman soldier left his dog suffering from arthritis in Dax, but on returning he found his dog in excellent health – thanks to the miraculous thermal water.

13th Century portal at Dax, preserved. The apostles are to right and left of the doorway, with St James to second from the right.

Today, a note on one of the further flung Ninian connections, demonstrating the devotion of expat Scots to their Saint who had acquired national standing by the 15th and 16th Centuries, and a bit more on the history of hot baths. We've spoken in a recent post about the preparation required for pilgrimage and the cost particularly of the longest and most arduous journeys, of which travel across the Pyrenees towards Compostela was and remains one of the great mediaeval pilgrim journeys. The merit of the longer journey on foot, rather than taking the shorter (more costly) sea route, was that spiritual benefits could be accrued on the way by visiting a multiplicity of other shrines, which are mentioned in the famous so-called Pilgrim's Guide, which forms the final book of the "Jacobus", a compilation of lives of Saint James of Compostela. The final book of the Codex Calixtinus ( its other name, after the Pope) describes the pilgrimage, with a chapter on roads through France, which meet at Puente la Reina. En route, accommodation was available in wayside hospitals, including that at Dax, just north of the Iberian frontier. Pilgrims from Scotland, having come on this long journey, must have felt at home, when they found the hospital here had, according to David Ditchburn, been either built or repaired by an expatriate pious and apparently patriotic Scot in the sixteenth century and it must surely have been an especial attraction that they could collect an indulgence by contributing to the hospital’s maintenance on the feast days of the Virgin, and Scotland's national saints, St Andrew and St Ninian (in this context of course, "hospital" has the mediaeval meaning derived from the Latin word hospitalis, meaning accommodating hospites, or guests - any persons who needed shelter). Dax (Aquae, Acqs, d'Acqs)at the time was thronged with pilgrims en route for Compostela, and it was richly supplied with jewellers' shops to make settings for the seashells which were symbols of the pilgrimage. Dax is still famed for its thermal water and the healing mud from the river Adour, which were believed to treat rheumatic and phlebological ailments. The “Fontaine Chaude” is a mineral spring erected on the ruins of the Roman bath. Today, on the main street, a marble trough has a row of Roman bronze lion heads with open mouths, and above it the columns of the Roman bath. The miracles of Dax began before the arrival of pilgrims, when, according to local legend, a Roman soldier left his dog suffering from arthritis in Dax, but on returning he found his dog in excellent health – thanks to the miraculous thermal water.

13th Century portal at Dax, preserved. The apostles are to right and left of the doorway, with St James to second from the right.