- Time of past OR future Camino

- Many, various, and continuing.

Dear friends, the Fraternidad Internacional del Camino de Santiago, an activist group comprised of historians, sociologists, hospitaleros, and camino busybodies, last weekend met in Sarria to debate the latest issues and decide how to solve some problems.

Most of you know that one of our more controversial proposals is petitioning the cathedral to extend the 100 km. required to earn a Compostela certificate to 300 kilometers. Everyone asks why.

So I translated (pretty awkwardly in places, I know!) the explanatory document, a paper written by Anton Pombo, a camino historian who has lived much of the current renaissance on the trail -- he was one of the first to paint yellow arrows to Finesterre. This document was presented to the cathedral dean and cabildo last week. It has NOT been approved or put into effect!

PROPOSAL TO EXPAND THE MINIMUM DISTANCE REQUIRED FOR AWARDING OF THE COMPOSTELA to 300 KILOMETERS

THE GENESIS OF THE ROAD

Since its inception, the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela was never a short-term undertaking. It was not a local or regional shrine that gradually gained fame through popular acclaim and miracles. On the contrary, it sprang into being with fully-formed international appeal: It led to the officially recognized apostolic tomb of Santiago the Greater. It managed to bring together not only Christian rites and symbols, but incorporated practices of past cults as well, as evidenced by legends of the translation of James’ body and the possible Celtic pilgrimage to Finisterre.

Alfonso II the Chaste, King of Asturias and Galicia, made the first political pilgrimage to Santiago after the rediscovery or "inventio" of the tomb between AD 820 and 830. The first documented pilgrims appeared in the 10th century from beyond the Pyrenees, devotees from from Germany and France, but we do not know their itinerary.

By the 11th century the “French route” along the Meseta was already established as a long-distance roadway to and from Europe, equipped with a network of pilgrim shelters. The pilgrimage to Santiago took its place alongside Jerusalem and Rome as one of the three great classic treks of Christianity. Santiago stood at the western end of the known world, following the direction the sun in the day and the Milky Way in the night. For pure symbolic value, Santiago surpassed Jerusalem and Rome. The Jacobean legend spread through Europe in the tales of Compostela in the times of Bishop Gelmirez, and above all, in the Codex Calixtinus. The universal dimension of this pilgrimage shines through medieval literature, inspiring works like the Historia Caroli Magni et Rotholandi or “Pseudo Turpin.” This book recounts the exploits of King Charlemagne, whose army supposedly opened the Camino pathway, guided by a sweep of stars all the way to Compostela and the ocean beyond.

The same tone was maintained into the late Middle Ages, despite the Reformation. The Counter-Reformation infused the pilgrimage with a focus on Catholic dogma. Walking to Santiago became a visible, living profession of religious faith. Pilgrims trickled in from all over the world. Centuries passed, but the Way of Santiago never lost its international character.

DECLINE AND REBIRTH OF THE PILGRIMAGE

But over time, the triumph of Liberal thought and the overwhelming idea of progress consigned the ancient pilgrimage path to a relic, something anachronistic and meaningless, reserved for vagrants and beggars. By the 19th century, the Compostela pilgrimage was practically extinct.

Other European Christian shrines and pilgrimages enjoyed a limited success, so archbishops Payá y Rico and Martin Herrera sought to stir up a new public religious devotion to St. James. The relics of the apostle were re-discovered after 300 years, so the local authorities tried to revitalize the pilgrimage with their meager means, using local processions and day-trips to Santiago as well as other holy sites, to at least keep the flame burning.

These local “romerias” became popular throughout Spain, upholding regional pride but thwarting the idea of traditional pilgrimage on foot. Twentieth-century “National Catholicism” manipulated the Compostela pilgrimage, focusing the faithful on arriving at the goal. The Way itself was downplayed, and the old walking routes were practically forgotten.

When the European Postwar intellectual and social crisis struck in the 1950s, it was foreigners, not Spaniards, who rediscovered the value of the pilgrimage. The Paris Society of Friends of the Camino was founded in 1950, with the Marquis Rene de La Coste-Messelière, among those who took the first timid steps.

The first Spanish association formed in Estella in the 1960s with the involvement of Paco Beruete and Eusebio Goicoechea, and registered itself in 1973. They delved into the study of the Jacobean pilgrimage as part of the Medieval Weeks festival in Estella, with their eyes always trained on the 11th and 12th-century "golden age" they hoped may someday revive.

This same historicist and romantic spirit, with the Codex Calixtinus as the main reference, is what inspired Elijah Valiña Sampedro, a man misunderstood in his time, to conceive the idea of revitalizing the foot pilgrimage on the French Way. Not beginning from Sarria, his own birthplace, nor from the Galician frontier, despite his being the pastor of St. Mary of O Cebreiro, Don Elias took the long view. He traced the most direct route to Compostela, gradually joining section to other sections. He understood from the beginning the Way in its original sense, as a geographic whole. Thus, with the collaboration of different people all along the route, he went to work to recover and mark with yellow arrows the better-known and documented French Way, from the Pyrenees to Compostela. He cooperated closely with the French, who did the same with France’s great historic routes, described in the famous guide book V of Calixtino: Tours, Vézelay, Le Puy and Arles.

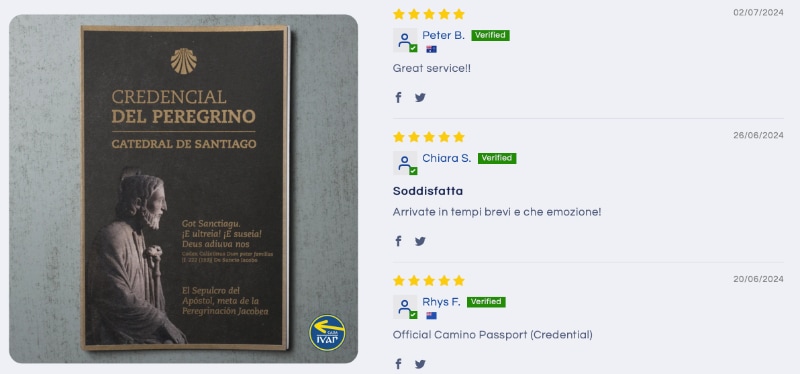

Thus was reborn the Camino de Santiago in the 70s and 80s of the last century, with the utmost respect for history and tradition. The French Way was recovered first, and the remaining historical itineraries soon followed. It was an exemplary process, performed selflessly from the bottom up with the support and generosity of associations of Friends of the Camino de Santiago, which multiplied since the 80s. The Amigos groups’ first major achievement was the International Congress of Associations of Jaca (1987), chaired by Elias Valiña as Commissioner of the Way. A new credential was established, drawn from a prototype from Estella, to serve as a safe-conduct to contemporary pilgrims, allowing the use of pilgrim accommodations. No minimum distance was established to claim a Compostela at the Cathedral.

FROM THE XACOBEO TO NOW

The year 1993 was a Holy Year, and pilgrims poured into the shrine city. The regional government of Galicia rolled out "Xacobeo," a secular, promotional program that claimed to “parallel” the religious celebration while developing advertising campaigns and marketing strategies. The Xacobeo slogan, "All the Way," summed-up its fundamental objective: to transform the Camino de Santiago into a great cultural and tourist brand for Galicia, and squeeze the maximum benefit from a tourist phenomenon ripe with possibilities for community development. It was at this point that the still-incipient mileage requirement of the Compostela was set at 100 km.

The "All the Way" and 100 km idea, despite Galicia’s good-faith construction of a public network of free shelters, immediately created tensions with the plan developed by Valiña and the worldwide Jacobean associations. The minimum distance, which fit perfectly into the plans of the Xunta de Galicia to “begin and end the Camino in Galicia,” ended up creating a distorted image of what and where the Camino de Santiago is, a distortion that appears now to be unstoppable, and threatens to undermine and trivialize the traditional sense of the Compostela pilgrimage. For many, the pilgrimage is understood only as a four- or five-day stroll through Galicia – a reductionist view antagonistic to the historical sense of the great European pilgrimage tradition.

This distortion has contributed to the ongoing transformation of the road into a tourist product. Tour operators and travel agencies offer the credential and Compostela as marketing tools, souvenirs that reward tourists and trekkers who walk four or five days of the road without any idea of pilgrimage, using and monopolizing the network of low-cost hostels intended for pilgrims. The consequence of this abuse is the same seen at by many sites of significant cultural heritage: the progressive conversion of the monument or site to a “decaffeinated” product of mass tourism. It is a theme park stripped of “boring” interpretive information from historians or literary scholars, suitable for the rapid entertainment of the new, illiterate traveler unable to see any value in an experience that is not immediately recognizable and familiar. The consumer cannot enjoy an experience that requires preparation, training, and time, so the marketers provide him with a cheap and easy “Camino Lite” experience. Likewise, even as the Camino is commodified, its precious, intangible heritage of interpersonal generosity and simplicity is lost. Without this “pilgrim spirit,” the Camino’s monumental itinerary becomes a mere archaeological stage-set.

In recent years, the number of pilgrims from Sarria, Tui, Lugo, Ourense, Ferrol and other places just beyond the 100 km required to obtain the Compostela, has grown steadily, according to data provided by the Pilgrimage Office of the Cathedral of Santiago. The true number of “short haul” pilgrims is, according to studies prepared by the Observatory of the Camino de Santiago USC, much higher. More than 260,000 pilgrims registered in 2015, but at least as many again did not register at the cathedral office – they had been on the road without reaching the goal (they ran out of time) or they did not collect the Compostela due to lack of interest or knowledge. Many of these unregistered "pilgrims" respond the low-cost tourist or hiker profile.

According to figures for 2015, of the 262,516 pilgrims who collected the Compostela, 90.19% arrived on foot. More than a quarter left from Sarria (25.68%, more than double the number who left from St. Jean-Pied-de-Port, a traditional starting point 500 km. away in France). Another 5.25% walked from Tui; 3.94% came from O Cebreiro (151 km); Ferrol 3.31%; 2.17% from Valenca do Minho; 1.17% from Lugo; Ourense 1.09%; 0.84% to 0.57% from Triacastela and Samos, to name the next major starting points. Add up all these “short haul” pilgrims, and you see they are 44.02%, almost half of the total. Their numbers rise each year. If we add to this figure those arriving from points far less than 300 km from Santiago de Compostela the number is well over 50% of registered pilgrims.

We are faced with a choice. This “short-trip pilgrim” dynamic is only slowed by foreign pilgrims, who naturally fit better into the traditional role of the long-haul pilgrimage. We can keep silent and give up the Camino to the short-term interests of politicians, developers and agencies seeking only immediate benefit or profits. Or we can resist, try to change the trend, redirect the Camino to its role as an adventure that has little to do with tourism. We can reclaim the long-distance Camino and the values that make it unique: effort, transcendence, searching, reflection, encounters with others, solidarity, ecumenism or spirituality, all of them oriented toward a distant, shared goal.

Some object, noting that long ago, every pilgrim started from his own home, no matter how near or far it was from Santiago. Documentation and history say that Santiago de Compostela was never a place of worship for the Galicians, who had their own shrines and pilgrimages. Outside the pilgrimage, Santiago never had a great relevance for Spaniards, let alone the majority of foreign pilgrims.

The FICS proposal to amend of the Compostela requirements by the Council of the Church of Santiago is not intended to solve at a stroke the problems of the Camino. Requiring a walk of 300 kilometers will not ease the overcrowding on the last sections, or stop the clash between two opposite ways of understanding the pilgrimage. It aims at the symbolic level, and hopes to establish a new understanding of the Way which dovetails with the traditions of the preceding eleven centuries .

1. We hope first to re-establish to dignity of the Compostela, which has lately become an increasingly devalued certificate granted without requirements or agreements attached. It is handed out as a prize or a souvenir at the end of a Camino de Santiago package tour, without a flicker of its religious or spiritual connotation.

2. The contemporary revival of the Camino has made every effort to restore and protect historic pilgrimage routes. The Camino trail is hailed for its cultural interest, and its heritage value is listed by UNESCO. The same care should be exercised should be taken to preserve the practices of the pilgrims on the Santiago trail – the “pilgrim spirit” that forms the Camino’s intangible heritage. Thousands of pilgrims still experience the unity and life-changing power of the trail in its utter simplicity. Their needs cannot be sacrificed to “inevitable concessions to modernity.”

3. Many Gallegos who profit from the Camino see the pilgrimage as a passing phenomenon. They take a short-sighted view of history, and disregard the efforts and claims of neighboring communities of Asturias and Castilla y Leon, and Portugal, all of which have striven to document, retrieve, waymark and revitalize their historic itineraries of the reborn pilgrimage. Despite what Gallego tourist authorities say, the Camino de Santiago does not begin at the Galician border. The road should be treated as a whole, not segmented into independent and disjointed portions, and even less monopolized by the end-point. Even more oddly, ancient camino routes are being marketed as a paths without a goal – a phenomenon apparent in France, or on tributary routes that converge with larger axis, (ie, the Aragonés Camino, Camino del Baztán, San Adrian Tunnel, etc.), sold as "Jacobean routes."

4. This proposed distance is fixed at about three hundred kilometers. This figure is not a random whim – it is drawn from the very first recorded pilgrimage route to Compostela, now known as Camino Primitivo. This is the route taken by the courtiers of Oviedo to the honor the relics of the “Locus Sancti Iacobi,” a distance of 319 km.

Likewise, the 300 km. distance also fits the subsequent 10th century shift of the main pilgrimage axis to the French Way. King Garcia moved his court from Oviedo to Leon, a move confirmed by Ordoño II. Leon is 311 kilometers from Santiago.

Other places linked to the pilgrimage also fit within the scope of this distance: Aviles (320 km), the main medieval port of Asturias, where seaborne pilgrims landed; Zamora (377 km) in the Via de la Plata; Porto (280 km) in the Central Portuguese Way; or the episcopal city of Lamego (290 km) on the Portuguese Way of the Interior.

5. The basis of our proposal is historical: The original geographic triangle of Aviles, Oviedo, Leon. There should therefore not be an arbitrary numerical figure, but a reasonable level of average distance for the traditional pilgrimage on foot, by bicycle or on horseback, in the vicinity of 300 km. This puts the spotlight on the different Jacobean long-distance routes. It meets the needs of contemporary pilgrims for good transportation links and population centers to launch them on their way.

6. The change is not intended to exclude pilgrims whose limited schedules prevent them from walking more than 100 km, an objection that always is posited against increasing the required mileage. The road can be done in stages, at different time periods, or very slowly, all of which are perfectly valid ways to obtain the Compostela.

7. Attempts to divert pilgrims from the overcrowded French Way and Portuguese Route have been unsuccessful, and there are still overcrowding problems on the final, Galician stages, especially from Tui and Sarria onward to Compostela. Municipalities along these roads face serious problems at times of peak pilgrim traffic.

8. The Galician administration’s appropriation of the Camino de Santiago and marketing efforts that describe only the last (Galician) 100 km, have left large areas of Galician Camino “high and dry:” Samos, Triacastela or O Cebreiro, on the French Way; Castroverde, Baleira and A Fonsagrada on the Primitivo; Ribadeo, Lourenzá, Mondoñedo, Abadín and Vilalba on the Northern Way; The whole province of Ourense east of the capital, Allariz, Xinzo, Verin, A Gudina, on the Sanabres Route. The citizens of these camino communities provide the same services to pilgrims, but are unfairly cut from the pilgrimage map by a regional administration so sharply focused on the 100-kilometer radius.

9. The 300-kilometer shift will ease the antagonism that rises up between long-distance pilgrims and those on a “short haul.” Attempts to turn the last stages of the Way into a pure tourist “Disneyland” will be blunted.

10. An exception must be made for the English Way, a route with historical documentation reaching back to the Late Middle Ages. Pilgrims came by sea to Ferrol (120 km) and A Coruña (75 km), now one of the most marginalized of all itineraries. Finally, another logical exception must be granted to disabled pilgrims, for whom the 100 km limit should continue.

The request to extend the 300 km the minimum for obtaining Compostela is part of a more ambitious global proposal. FICS proposes a new management model for public shelters, with preference given to long-haul pilgrims, and eliminating abuses by commercial interests who profit from the albergue network. Government bodies should stop viewing the pilgrimage to Santiago as a tourist product or leisure experience. It is imperative that management and promotion of the Camino be removed from the Tourism department and returned to the oversight of Culture and Heritage.

We view The Way in its original medieval incarnation, as a great long-haul odyssey. The current dynamic strips away the meaning of the Camino for the sake of pecuniary interests and inevitably leads to a complete break with tradition. Those of us who work on and for the Camino – Amigos Associations, albergues, volunteers, government agents, and the Compostela cathedral itself -- are directly responsible for preventing this process of consumption. Our position is not just a romantic notion, much less a reactionary stand. It is made from deep respect for an ancient tradition that some shortsighted people are distorting for the sake of economic opportunism. If we do not stand up, they will soon destroy the magic that is the Camino de Santiago.

Anton Pombo, International Brotherhood of Camino de Santiago.

Sarria, March 12, 2016

Most of you know that one of our more controversial proposals is petitioning the cathedral to extend the 100 km. required to earn a Compostela certificate to 300 kilometers. Everyone asks why.

So I translated (pretty awkwardly in places, I know!) the explanatory document, a paper written by Anton Pombo, a camino historian who has lived much of the current renaissance on the trail -- he was one of the first to paint yellow arrows to Finesterre. This document was presented to the cathedral dean and cabildo last week. It has NOT been approved or put into effect!

PROPOSAL TO EXPAND THE MINIMUM DISTANCE REQUIRED FOR AWARDING OF THE COMPOSTELA to 300 KILOMETERS

THE GENESIS OF THE ROAD

Since its inception, the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela was never a short-term undertaking. It was not a local or regional shrine that gradually gained fame through popular acclaim and miracles. On the contrary, it sprang into being with fully-formed international appeal: It led to the officially recognized apostolic tomb of Santiago the Greater. It managed to bring together not only Christian rites and symbols, but incorporated practices of past cults as well, as evidenced by legends of the translation of James’ body and the possible Celtic pilgrimage to Finisterre.

Alfonso II the Chaste, King of Asturias and Galicia, made the first political pilgrimage to Santiago after the rediscovery or "inventio" of the tomb between AD 820 and 830. The first documented pilgrims appeared in the 10th century from beyond the Pyrenees, devotees from from Germany and France, but we do not know their itinerary.

By the 11th century the “French route” along the Meseta was already established as a long-distance roadway to and from Europe, equipped with a network of pilgrim shelters. The pilgrimage to Santiago took its place alongside Jerusalem and Rome as one of the three great classic treks of Christianity. Santiago stood at the western end of the known world, following the direction the sun in the day and the Milky Way in the night. For pure symbolic value, Santiago surpassed Jerusalem and Rome. The Jacobean legend spread through Europe in the tales of Compostela in the times of Bishop Gelmirez, and above all, in the Codex Calixtinus. The universal dimension of this pilgrimage shines through medieval literature, inspiring works like the Historia Caroli Magni et Rotholandi or “Pseudo Turpin.” This book recounts the exploits of King Charlemagne, whose army supposedly opened the Camino pathway, guided by a sweep of stars all the way to Compostela and the ocean beyond.

The same tone was maintained into the late Middle Ages, despite the Reformation. The Counter-Reformation infused the pilgrimage with a focus on Catholic dogma. Walking to Santiago became a visible, living profession of religious faith. Pilgrims trickled in from all over the world. Centuries passed, but the Way of Santiago never lost its international character.

DECLINE AND REBIRTH OF THE PILGRIMAGE

But over time, the triumph of Liberal thought and the overwhelming idea of progress consigned the ancient pilgrimage path to a relic, something anachronistic and meaningless, reserved for vagrants and beggars. By the 19th century, the Compostela pilgrimage was practically extinct.

Other European Christian shrines and pilgrimages enjoyed a limited success, so archbishops Payá y Rico and Martin Herrera sought to stir up a new public religious devotion to St. James. The relics of the apostle were re-discovered after 300 years, so the local authorities tried to revitalize the pilgrimage with their meager means, using local processions and day-trips to Santiago as well as other holy sites, to at least keep the flame burning.

These local “romerias” became popular throughout Spain, upholding regional pride but thwarting the idea of traditional pilgrimage on foot. Twentieth-century “National Catholicism” manipulated the Compostela pilgrimage, focusing the faithful on arriving at the goal. The Way itself was downplayed, and the old walking routes were practically forgotten.

When the European Postwar intellectual and social crisis struck in the 1950s, it was foreigners, not Spaniards, who rediscovered the value of the pilgrimage. The Paris Society of Friends of the Camino was founded in 1950, with the Marquis Rene de La Coste-Messelière, among those who took the first timid steps.

The first Spanish association formed in Estella in the 1960s with the involvement of Paco Beruete and Eusebio Goicoechea, and registered itself in 1973. They delved into the study of the Jacobean pilgrimage as part of the Medieval Weeks festival in Estella, with their eyes always trained on the 11th and 12th-century "golden age" they hoped may someday revive.

This same historicist and romantic spirit, with the Codex Calixtinus as the main reference, is what inspired Elijah Valiña Sampedro, a man misunderstood in his time, to conceive the idea of revitalizing the foot pilgrimage on the French Way. Not beginning from Sarria, his own birthplace, nor from the Galician frontier, despite his being the pastor of St. Mary of O Cebreiro, Don Elias took the long view. He traced the most direct route to Compostela, gradually joining section to other sections. He understood from the beginning the Way in its original sense, as a geographic whole. Thus, with the collaboration of different people all along the route, he went to work to recover and mark with yellow arrows the better-known and documented French Way, from the Pyrenees to Compostela. He cooperated closely with the French, who did the same with France’s great historic routes, described in the famous guide book V of Calixtino: Tours, Vézelay, Le Puy and Arles.

Thus was reborn the Camino de Santiago in the 70s and 80s of the last century, with the utmost respect for history and tradition. The French Way was recovered first, and the remaining historical itineraries soon followed. It was an exemplary process, performed selflessly from the bottom up with the support and generosity of associations of Friends of the Camino de Santiago, which multiplied since the 80s. The Amigos groups’ first major achievement was the International Congress of Associations of Jaca (1987), chaired by Elias Valiña as Commissioner of the Way. A new credential was established, drawn from a prototype from Estella, to serve as a safe-conduct to contemporary pilgrims, allowing the use of pilgrim accommodations. No minimum distance was established to claim a Compostela at the Cathedral.

FROM THE XACOBEO TO NOW

The year 1993 was a Holy Year, and pilgrims poured into the shrine city. The regional government of Galicia rolled out "Xacobeo," a secular, promotional program that claimed to “parallel” the religious celebration while developing advertising campaigns and marketing strategies. The Xacobeo slogan, "All the Way," summed-up its fundamental objective: to transform the Camino de Santiago into a great cultural and tourist brand for Galicia, and squeeze the maximum benefit from a tourist phenomenon ripe with possibilities for community development. It was at this point that the still-incipient mileage requirement of the Compostela was set at 100 km.

The "All the Way" and 100 km idea, despite Galicia’s good-faith construction of a public network of free shelters, immediately created tensions with the plan developed by Valiña and the worldwide Jacobean associations. The minimum distance, which fit perfectly into the plans of the Xunta de Galicia to “begin and end the Camino in Galicia,” ended up creating a distorted image of what and where the Camino de Santiago is, a distortion that appears now to be unstoppable, and threatens to undermine and trivialize the traditional sense of the Compostela pilgrimage. For many, the pilgrimage is understood only as a four- or five-day stroll through Galicia – a reductionist view antagonistic to the historical sense of the great European pilgrimage tradition.

This distortion has contributed to the ongoing transformation of the road into a tourist product. Tour operators and travel agencies offer the credential and Compostela as marketing tools, souvenirs that reward tourists and trekkers who walk four or five days of the road without any idea of pilgrimage, using and monopolizing the network of low-cost hostels intended for pilgrims. The consequence of this abuse is the same seen at by many sites of significant cultural heritage: the progressive conversion of the monument or site to a “decaffeinated” product of mass tourism. It is a theme park stripped of “boring” interpretive information from historians or literary scholars, suitable for the rapid entertainment of the new, illiterate traveler unable to see any value in an experience that is not immediately recognizable and familiar. The consumer cannot enjoy an experience that requires preparation, training, and time, so the marketers provide him with a cheap and easy “Camino Lite” experience. Likewise, even as the Camino is commodified, its precious, intangible heritage of interpersonal generosity and simplicity is lost. Without this “pilgrim spirit,” the Camino’s monumental itinerary becomes a mere archaeological stage-set.

In recent years, the number of pilgrims from Sarria, Tui, Lugo, Ourense, Ferrol and other places just beyond the 100 km required to obtain the Compostela, has grown steadily, according to data provided by the Pilgrimage Office of the Cathedral of Santiago. The true number of “short haul” pilgrims is, according to studies prepared by the Observatory of the Camino de Santiago USC, much higher. More than 260,000 pilgrims registered in 2015, but at least as many again did not register at the cathedral office – they had been on the road without reaching the goal (they ran out of time) or they did not collect the Compostela due to lack of interest or knowledge. Many of these unregistered "pilgrims" respond the low-cost tourist or hiker profile.

According to figures for 2015, of the 262,516 pilgrims who collected the Compostela, 90.19% arrived on foot. More than a quarter left from Sarria (25.68%, more than double the number who left from St. Jean-Pied-de-Port, a traditional starting point 500 km. away in France). Another 5.25% walked from Tui; 3.94% came from O Cebreiro (151 km); Ferrol 3.31%; 2.17% from Valenca do Minho; 1.17% from Lugo; Ourense 1.09%; 0.84% to 0.57% from Triacastela and Samos, to name the next major starting points. Add up all these “short haul” pilgrims, and you see they are 44.02%, almost half of the total. Their numbers rise each year. If we add to this figure those arriving from points far less than 300 km from Santiago de Compostela the number is well over 50% of registered pilgrims.

We are faced with a choice. This “short-trip pilgrim” dynamic is only slowed by foreign pilgrims, who naturally fit better into the traditional role of the long-haul pilgrimage. We can keep silent and give up the Camino to the short-term interests of politicians, developers and agencies seeking only immediate benefit or profits. Or we can resist, try to change the trend, redirect the Camino to its role as an adventure that has little to do with tourism. We can reclaim the long-distance Camino and the values that make it unique: effort, transcendence, searching, reflection, encounters with others, solidarity, ecumenism or spirituality, all of them oriented toward a distant, shared goal.

Some object, noting that long ago, every pilgrim started from his own home, no matter how near or far it was from Santiago. Documentation and history say that Santiago de Compostela was never a place of worship for the Galicians, who had their own shrines and pilgrimages. Outside the pilgrimage, Santiago never had a great relevance for Spaniards, let alone the majority of foreign pilgrims.

The FICS proposal to amend of the Compostela requirements by the Council of the Church of Santiago is not intended to solve at a stroke the problems of the Camino. Requiring a walk of 300 kilometers will not ease the overcrowding on the last sections, or stop the clash between two opposite ways of understanding the pilgrimage. It aims at the symbolic level, and hopes to establish a new understanding of the Way which dovetails with the traditions of the preceding eleven centuries .

1. We hope first to re-establish to dignity of the Compostela, which has lately become an increasingly devalued certificate granted without requirements or agreements attached. It is handed out as a prize or a souvenir at the end of a Camino de Santiago package tour, without a flicker of its religious or spiritual connotation.

2. The contemporary revival of the Camino has made every effort to restore and protect historic pilgrimage routes. The Camino trail is hailed for its cultural interest, and its heritage value is listed by UNESCO. The same care should be exercised should be taken to preserve the practices of the pilgrims on the Santiago trail – the “pilgrim spirit” that forms the Camino’s intangible heritage. Thousands of pilgrims still experience the unity and life-changing power of the trail in its utter simplicity. Their needs cannot be sacrificed to “inevitable concessions to modernity.”

3. Many Gallegos who profit from the Camino see the pilgrimage as a passing phenomenon. They take a short-sighted view of history, and disregard the efforts and claims of neighboring communities of Asturias and Castilla y Leon, and Portugal, all of which have striven to document, retrieve, waymark and revitalize their historic itineraries of the reborn pilgrimage. Despite what Gallego tourist authorities say, the Camino de Santiago does not begin at the Galician border. The road should be treated as a whole, not segmented into independent and disjointed portions, and even less monopolized by the end-point. Even more oddly, ancient camino routes are being marketed as a paths without a goal – a phenomenon apparent in France, or on tributary routes that converge with larger axis, (ie, the Aragonés Camino, Camino del Baztán, San Adrian Tunnel, etc.), sold as "Jacobean routes."

4. This proposed distance is fixed at about three hundred kilometers. This figure is not a random whim – it is drawn from the very first recorded pilgrimage route to Compostela, now known as Camino Primitivo. This is the route taken by the courtiers of Oviedo to the honor the relics of the “Locus Sancti Iacobi,” a distance of 319 km.

Likewise, the 300 km. distance also fits the subsequent 10th century shift of the main pilgrimage axis to the French Way. King Garcia moved his court from Oviedo to Leon, a move confirmed by Ordoño II. Leon is 311 kilometers from Santiago.

Other places linked to the pilgrimage also fit within the scope of this distance: Aviles (320 km), the main medieval port of Asturias, where seaborne pilgrims landed; Zamora (377 km) in the Via de la Plata; Porto (280 km) in the Central Portuguese Way; or the episcopal city of Lamego (290 km) on the Portuguese Way of the Interior.

5. The basis of our proposal is historical: The original geographic triangle of Aviles, Oviedo, Leon. There should therefore not be an arbitrary numerical figure, but a reasonable level of average distance for the traditional pilgrimage on foot, by bicycle or on horseback, in the vicinity of 300 km. This puts the spotlight on the different Jacobean long-distance routes. It meets the needs of contemporary pilgrims for good transportation links and population centers to launch them on their way.

6. The change is not intended to exclude pilgrims whose limited schedules prevent them from walking more than 100 km, an objection that always is posited against increasing the required mileage. The road can be done in stages, at different time periods, or very slowly, all of which are perfectly valid ways to obtain the Compostela.

7. Attempts to divert pilgrims from the overcrowded French Way and Portuguese Route have been unsuccessful, and there are still overcrowding problems on the final, Galician stages, especially from Tui and Sarria onward to Compostela. Municipalities along these roads face serious problems at times of peak pilgrim traffic.

8. The Galician administration’s appropriation of the Camino de Santiago and marketing efforts that describe only the last (Galician) 100 km, have left large areas of Galician Camino “high and dry:” Samos, Triacastela or O Cebreiro, on the French Way; Castroverde, Baleira and A Fonsagrada on the Primitivo; Ribadeo, Lourenzá, Mondoñedo, Abadín and Vilalba on the Northern Way; The whole province of Ourense east of the capital, Allariz, Xinzo, Verin, A Gudina, on the Sanabres Route. The citizens of these camino communities provide the same services to pilgrims, but are unfairly cut from the pilgrimage map by a regional administration so sharply focused on the 100-kilometer radius.

9. The 300-kilometer shift will ease the antagonism that rises up between long-distance pilgrims and those on a “short haul.” Attempts to turn the last stages of the Way into a pure tourist “Disneyland” will be blunted.

10. An exception must be made for the English Way, a route with historical documentation reaching back to the Late Middle Ages. Pilgrims came by sea to Ferrol (120 km) and A Coruña (75 km), now one of the most marginalized of all itineraries. Finally, another logical exception must be granted to disabled pilgrims, for whom the 100 km limit should continue.

The request to extend the 300 km the minimum for obtaining Compostela is part of a more ambitious global proposal. FICS proposes a new management model for public shelters, with preference given to long-haul pilgrims, and eliminating abuses by commercial interests who profit from the albergue network. Government bodies should stop viewing the pilgrimage to Santiago as a tourist product or leisure experience. It is imperative that management and promotion of the Camino be removed from the Tourism department and returned to the oversight of Culture and Heritage.

We view The Way in its original medieval incarnation, as a great long-haul odyssey. The current dynamic strips away the meaning of the Camino for the sake of pecuniary interests and inevitably leads to a complete break with tradition. Those of us who work on and for the Camino – Amigos Associations, albergues, volunteers, government agents, and the Compostela cathedral itself -- are directly responsible for preventing this process of consumption. Our position is not just a romantic notion, much less a reactionary stand. It is made from deep respect for an ancient tradition that some shortsighted people are distorting for the sake of economic opportunism. If we do not stand up, they will soon destroy the magic that is the Camino de Santiago.

Anton Pombo, International Brotherhood of Camino de Santiago.

Sarria, March 12, 2016